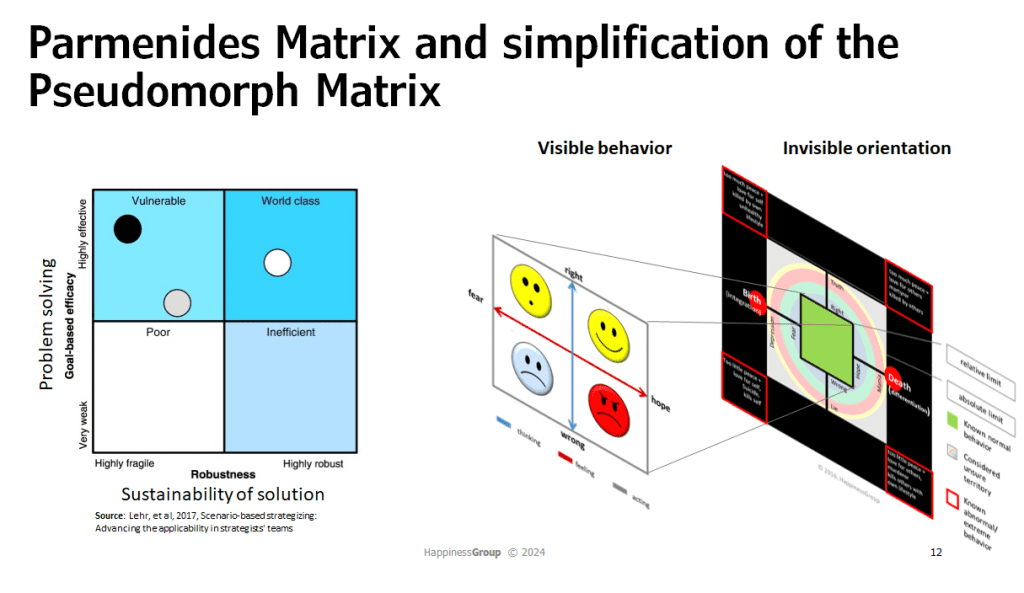

Parmenides matrix

The Parmenides Matrix is a philosophical tool attributed to the ancient Greek thinker Parmenides, used to explore the complexities of being and not-being. It consists of a grid that juxtaposes “what is” and “what is not” against various conditions of existence and thought. This matrix helps in dissecting and understanding the nature of reality, existence, and the limitations of human perception and reasoning. It delves into the paradoxes and challenges inherent in defining existence and non-existence, highlighting the intricate relationship between thought, language, and the nature of reality. This matrix serves as a foundational framework in metaphysics, aiding in the exploration of the fundamental nature of being.

What is life?

High performance and pathology often lie close together in the context of life due to the delicate balance between optimal functioning and the potential for dysfunction. This juxtaposition is rooted in the concept of biological and psychological trade-offs. In the pursuit of high performance, whether it be physical, mental, or evolutionary, organisms often push their limits to the edge of their functional capabilities. For instance, in humans, intense intellectual or athletic training can lead to remarkable achievements, but such extreme levels of performance can also strain the body and mind, increasing the risk of injury or psychological stress disorders. Similarly, in evolutionary terms, traits that confer an advantage in one aspect can lead to vulnerabilities in another, a phenomenon known as an evolutionary trade-off. For example, a highly specialized trait might improve survival under certain conditions but may become a liability if the environment changes. This close proximity between high performance and pathology illustrates a fundamental principle of life: the pursuit of excellence or adaptation often comes with inherent risks, and maintaining a balance is key to sustainability and health.

Performance and Pathology

Performance and pathology are related concepts that differ only in terms of duration and intensity. In other words, all humans exhibit pathological observables sometimes, but not long enough and not intense enough to qualify as clinical disorder.

After having defined the perfect human in the previous modules, we have reached the edge of genius space, the tipping point so to speak, when something good suddenly turns bad.

Clinically, a psychological disorder is defined with certain states in which an individual is unable to self-sustain her or himself.

Self-sustainability is dependent on shared – or common aspects of reality constructs. The less our own reality construct is compatible with the one’s from other humans, the more social interactions become difficult. Hence, the most important first question in any problem solving process is: “Who is crazy – me or the others”?

Xia et al. in her article describes the four bio-marker that determine alone or in combination with each other all psychological disorders. They also nicely align with the Axis Classification schema of the DSM-V, developed by Kraepelin.

Assuming that the purpose of life is encoded in the intelligence algorithm of a single cell and reads: learn, grow, transform, we can assume that any condition violating that rule must be considered toxic. Up to a certain level of toxicity of an environment it can still be fun, but it is not sustainable.

The biomarker identified by Xia can be compared to defects in crystals, information distortion in encryption or configuration errors in logical gates due to missing or falsely connected nodes in a neural network. When the amount of defects passes a certain threshold, we develop clinically relevant symptoms.

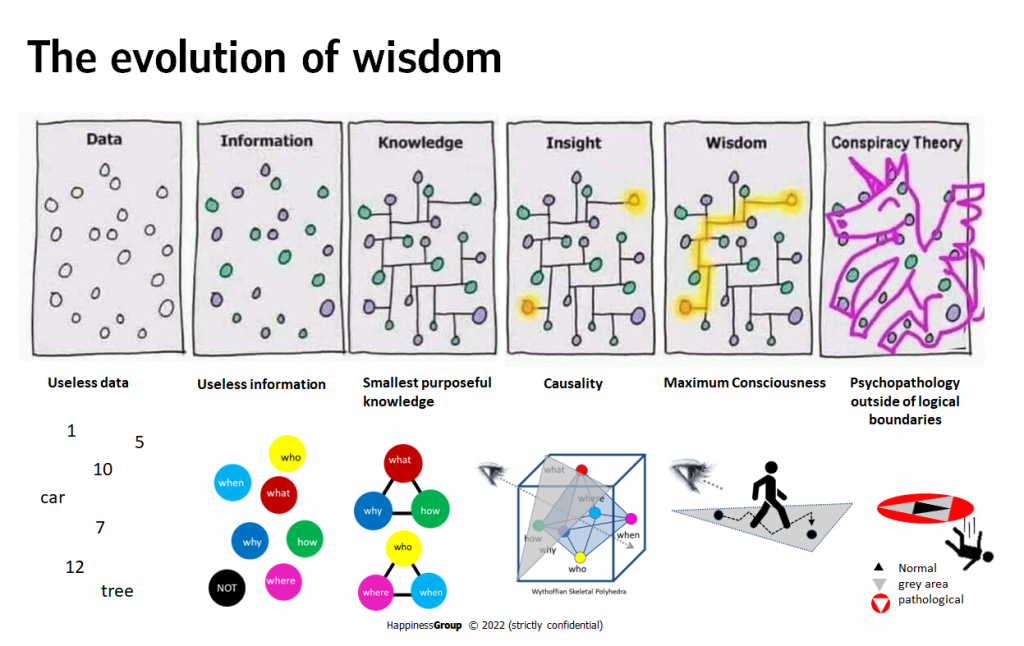

Generally speaking there are only two possible informational problem states that lead to overcounting past or future for the path integral over kowledge and belief:

a) too much information –> leading to misunderstandings

b) too little information –> leading to false assumptions

Both lead to false expectations.